2,057 words, 11 minutes read time.

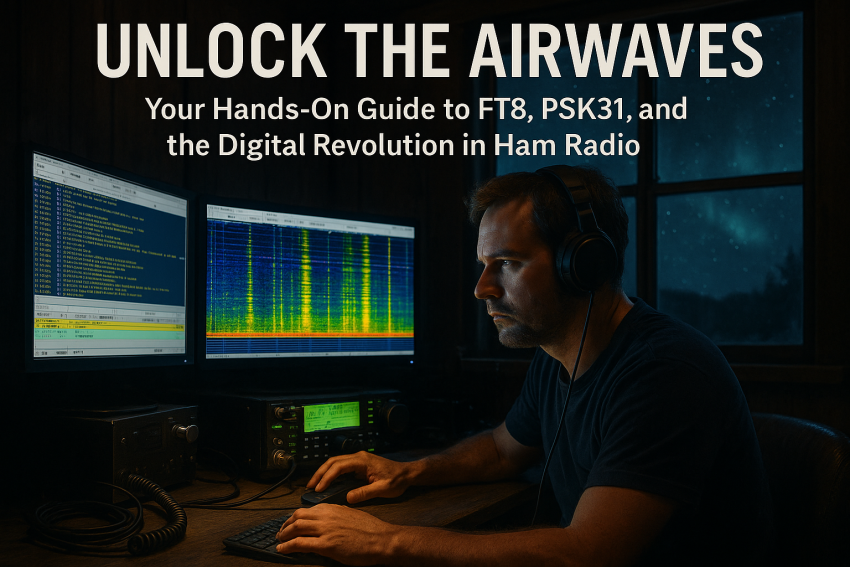

Hey brother, if you’ve ever stared at a waterfall display full of squiggly lines and felt that tug of curiosity—like there’s a whole secret conversation happening just out of earshot—this guide is for you. I’m the guy who’s been elbow-deep in coax and code for longer than I care to admit, and I’m here to walk you through the digital side of amateur radio the way I wish someone had walked me through it twenty years ago. No fluff, no gatekeeping, just straight talk from one operator to another about why modes like FT8 and PSK31 are the fastest way to turn a quiet receiver into a global DX machine. By the time you finish reading, you’ll know exactly how to fire up your rig, sync your clock, and work Japan on five watts while the coffee’s still hot. Let’s get after it.

Why Digital Modes Are the Modern Ham’s Secret Weapon

Picture this: it’s 2 a.m., the bands are dead, and your buddy on SSB is yelling into the void with a kilowatt and still coming up empty. Meanwhile, you’re sipping a cold one, watching FT8 decode stations from Antarctica on a dipole in the attic running thirty watts. That’s not science fiction—that’s Tuesday night for thousands of us. Digital modes aren’t just another tool in the shack; they’re the great equalizer. They let you punch way above your power class, work rare grid squares from a city lot, and rack up confirmations without ever needing to growl “CQ” into a microphone. Joe Taylor, K1JT—the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who literally wrote the book on weak-signal work—once said in an interview with the ARRL, “FT8 was designed to be the mode you use when everything else fails.” And brother, when the sunspots are asleep, everything else does fail. But FT8? It keeps right on trucking. The magic is in the math: forward error correction, precise timing, and a signal so narrow it slips between the noise like a knife. You don’t need a tower or a linear. You need a radio, a laptop, and the willingness to let the software do the heavy lifting while you kick back and watch the countries roll in.

The Nuts and Bolts: How Digital Turns Sound Into Data

Let’s peel back the curtain before we spin a single knob. At its core, every digital mode is just your radio turning audio tones into ones and zeros, then sending those bits out as precisely timed squawks. Your sound card is the translator. Feed it the warbly output from your rig’s speaker jack, and software like WSJT-X or FLdigi turns that mess of noise into readable text faster than you can say “73.” The beauty is you don’t need a Ph.D. in signal processing to make it work. A ten-dollar USB audio dongle and a couple of patch cables get you on the air. I still remember my first digital contact—PSK31 with a guy in Finland on forty meters using nothing more than an old Dell laptop and a homemade interface built from RadioShack parts. The signal was barely a whisper above the static, but there it was, plain as day: his call, his name, even the temperature in Helsinki. That moment hooked me harder than any phone QSO ever did. The takeaway? Digital doesn’t care about your voice, your accent, or your mic fright. It only cares that your clock is within a second of UTC and your audio levels aren’t clipping. Get those two things right, and the world opens up.

FT8: The 15-Second Miracle That Rewrote DXing

If digital modes were a boxing weight class, FT8 would be the heavyweight champ that nobody saw coming. Launched in 2017, it exploded across the bands so fast that the ARRL had to rewrite their contest rules to keep up. The cycle is brutally elegant: fifteen seconds to transmit, fifteen to receive, repeat. In that window, you send 13 characters—call signs, grid, signal report—and the protocol’s Reed-Solomon error correction rebuilds the message even when half the bits are drowned in noise. I’ve worked VK6 on eighty meters with the S-meter barely twitching, and the confirmation showed up in Logbook of the World before I finished logging the contact. Setting up is straightforward. Download WSJT-X from the official site, plug in your rig via USB or a SignaLink, and let the software control frequency and PTT. The first hurdle most guys hit is time sync—your computer’s clock has to be within one second of internet time or the decodes turn to garbage. I run Meinberg NTP in the background; it’s set-it-and-forget-it. Next, pick a clear frequency. On twenty meters, 14.074 MHz is the FT8 watering hole. You’ll see the waterfall light up like the Vegas strip at happy hour. Click a CQ, hit Enable TX, and watch the macro sequence do its thing. Four exchanges later you’re in the log. Pro tip: keep your power under thirty watts. The duty cycle is 100 %, and anything more just heats the finals without buying you decodes. As one old-timer on the WSJT mailing list put it, “FT8 is like fishing with dynamite—except the fish jump in the boat and thank you for the ride.”

PSK31: Where the Conversation Actually Feels Like Talking

Now, FT8 is efficient, but sometimes you want to shoot the breeze instead of firing off postcards. That’s where PSK31 shines. Born in the late ’90s by Peter Martinez, G3PLX, it was the original keyboard-to-keyboard mode, and it still holds its own. The signal is a razor-thin 31 Hz wide—narrower than a CW note—and it thrives in the noise. Fire up FLdigi, tune to 14.070 MHz, and you’ll see a dozen conversations stacked like cordwood. Unlike FT8’s rigid timing, PSK31 is free-flowing. You type, it sends. He types, you read. Macros handle the boilerplate—“name here is Mike QTH Colorado rig is IC-7300 antenna is end-fed half-wave”—but the meat of the QSO is live. I worked a guy in Siberia one winter night who described the northern lights in real time while I watched the same green glow out my shack window. That’s the magic you don’t get with automated modes. Setup is dead simple: same sound-card interface, same low power. The trick is keeping your ALC in check—PSK hates distortion the way a chef hates a dull knife. Set your mic gain so the ALC needle never twitches, and you’ll copy stations that sound like whispers in a hurricane. If you’re the type who enjoys a ragchew without the spotlight of a microphone, PSK31 is your new best friend.

Beyond the Big Two: A Quick Tour of the Digital Playground

Once FT8 and PSK31 are in your toolkit, the door cracks open to a dozen other modes worth exploring. JT65 and JT9, the older siblings of FT8, use one-minute cycles and are still the go-to for moonbounce and meteor scatter. WSPR—pronounced “whisper”—turns your rig into a propagation beacon. Run five watts into a decent antenna, and the WSPRnet map will show you who heard you halfway around the planet. I once fired up WSPR on two meters from a hotel balcony in Denver and spotted a station in Kansas 400 miles away on a rubber duck. RTTY, the granddaddy of digital, still rules contests with its clacking Baudot code and forgiving nature. And then there’s Olivia, the bulldog of noisy bands—slow as molasses but copies through auroral flutter that buries everything else. Each mode is a different tool in the chest. Learn a couple, and you’ll never be off the air, no matter what the ionosphere throws at you.

Building the Digital Shack Without Breaking the Bank

You don’t need a moonshot budget to go digital. Start with any HF rig that has a data or SSB mode—my first digital station was an old Kenwood TS-520S that belonged to my grandfather. Add a $40 USB sound card interface, a laptop running Linux or Windows, and you’re 90 % there. Antennas? A resonant dipole at thirty feet outperforms a beam at ten when you’re running QRP digital. I’ve worked transatlantic on a 20-meter hamstick taped to a painter’s pole. Power supply noise is the silent killer—ferrite on everything, and keep switching wall-warts out of the shack. Time sync is non-negotiable; a $20 GPS puck feeding NTP is cheap insurance. And logging? LoTW and QRZ make paper logs obsolete. Upload your ADIF file after a session, and the confirmations roll in while you sleep. The entire station can live in a ammo can for portable ops—radio, netbook, LiFePO4 battery, and a roll-up end-fed. I’ve run Field Day from a picnic table with that exact kit and outscored stations running generators and towers.

Pro Tips From the Trenches

Here’s the stuff they don’t put in the manuals. First, never transmit with the waterfall zoomed out too far—you’ll step on someone. Second, check pskreporter.info before you call CQ; if the map shows you being heard in Europe, go for it. Third, learn to read the FT8 message sequence: even-numbered minutes you transmit first if you’re calling CQ on a clear slot. Fourth, keep a notepad for frequency discipline—write down where the DXpeditions hang out, because 14.074 is a zoo during a contest. Fifth, experiment with receive-only on a web SDR if your local noise floor is brutal; I’ve decoded FT8 from a KiwiSDR in Hawaii while my city lot was under power-line hash. And finally, don’t chase signal reports. A -20 dB contact counts the same as a +10 in the log, and it builds character.

Leveling Up: From Wallflower to Contester

Once you’ve got a handful of digital QSOs under your belt, the next rush is calling CQ and watching the pileup form. Start with FT8 during a gray-line opening—sunrise in Japan is prime time from the U.S. West Coast. Move to PSK31 on a quiet weekday evening when the contesters are asleep. Then dip a toe into digital contests: the ARRL RTTY Roundup in January is forgiving, and the CQ WW DX Digital in June is a blast. After that, chase awards—Worked All States on digital is easier than you think when Alaska and Hawaii light up on forty meters at dawn. Build a go-kit and operate parks-on-the-air; the combination of low power and digital efficiency is tailor-made for portable. And when you’re ready for the deep end, try JS8Call—it’s FT8 with a messaging layer that lets you chat off-grid during emergencies. The progression is addictive: monitor, respond, initiate, dominate.

The Future Is Already Here

Look ahead five years, and digital will only get wilder. FT4 is already shaving FT8 cycles to 7.5 seconds for contest sprinting. VarAC blends chat with weak-signal magic. And researchers are experimenting with AI that predicts propagation and auto-selects the best mode. But the core truth won’t change: digital rewards precision over brute force. Master it now, and you’ll be the guy everyone asks for advice when the next sunspot minimum hits.

Brother, the bands are waiting. Download WSJT-X tonight, sync your clock, and tune to 14.074. Your first digital contact is fifteen seconds away, and it’ll feel like shaking hands across the planet. When you make it, drop a comment below and tell me where you worked—I read every one.

Call to Action

If this story caught your attention, don’t just scroll past. Join the community—men sharing skills, stories, and experiences. Subscribe for more posts like this, drop a comment about your projects or lessons learned, or reach out and tell me what you’re building or experimenting with. Let’s grow together.

Sources

- ARRL – PSK31 Operating

- RSGB – PSK31 Guide

- FT8 Protocol Details by K1JT

- PSK31 Basics by W8WWY

- Ham Radio Operators – Complete FT8 Guide

- Ham Radio Prep – Digital Modes Overview

- YouTube: FT8 Tutorial by K0PIR

- DXZone – FT8 Resources Collection

- ARRL Digital Modes PDF Handbook

- QRZ – Introduction to Digital Modes

- Ham Radio School – FT8 and Beyond

- ADIF Specification (for logging digital contacts)

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the author. The information provided is based on personal research, experience, and understanding of the subject matter at the time of writing. Readers should consult relevant experts or authorities for specific guidance related to their unique situations.