2,475 words, 13 minutes read time.

If you’ve ever stared at a SharePoint page wondering why your web part rendered twice, or why a click handler kept firing after you navigated away, you’ve felt the cost of not owning the lifecycle. I’ve been there, shipped the bugs, and paid the sleep tax. The BaseClientSideWebPart gives you a small but powerful set of hooks that decide when your code runs, when the DOM is safe to touch, when to fetch data, and when to clean up. When you treat those hooks like contractual boundaries instead of suggestions, your code gets faster, cleaner, and way more predictable.

I’m writing this for devs who want to get web parts under control without overengineering. I’ll stick to the basics the framework guarantees, with just enough seasoning from real projects where async initialization, property panes, and cleanup tend to bite. The point isn’t to memorize method names. It’s to internalize where each responsibility lives so your mental stack stops thrashing and you ship calmer.

I’ll assume SharePoint Online with SPFx 1.18.x, Node.js 16 LTS, TypeScript 4.x, and React 17 available in the toolchain even though the core lifecycle discussion applies whether you use React or go framework-free. If you’re on older on‑prem environments, some APIs might differ, but the lifecycle shape is the same. I’ll also assume you’re comfortable with TypeScript and the SPFx generator so we can stay focused on the lifecycle.

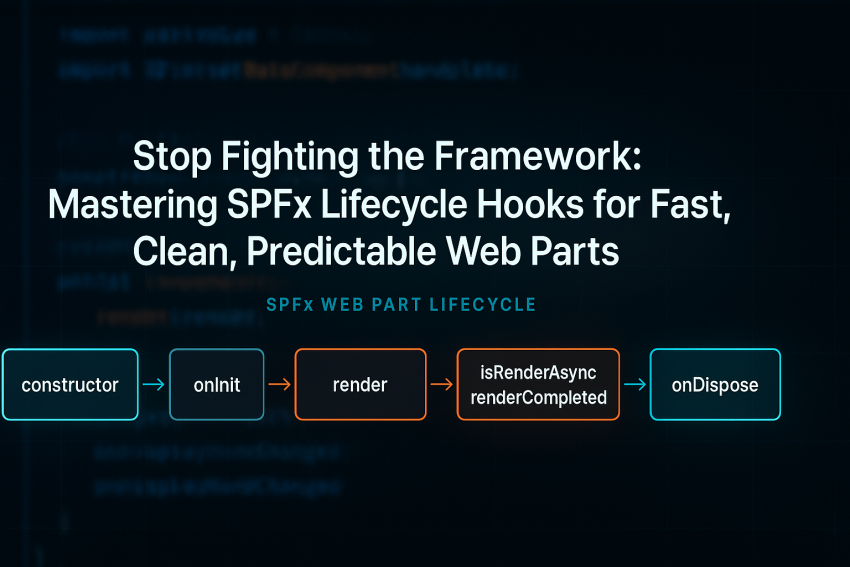

Here’s the mental model that finally made this click for me. Your web part class isn’t a component in the React sense. It’s a host that the framework instantiates once per web part instance on the page. SPFx constructs your class, sets up the context, calls onInit for asynchronous bootstrapping, and then calls render to let you populate the DOM. SPFx can call render multiple times whenever configuration changes or the display mode flips, so your render method has to be idempotent, side‑effect free, and fast. If you opt into asynchronous rendering, you tell SPFx that you’ll call renderCompleted once you’re done so it can clear the “loading” UX. When the page or the web part is torn down, onDispose is your chance to unhook event handlers and release resources. It’s a predictable dance if you let each step do one job.

To make the dance concrete, here’s the minimal timeline the framework runs. You can think of it like a tiny state machine per web part instance, and the order matters.

Page loads → SPFx creates your class

↳ constructor() [don’t touch the DOM]

↳ onInit() [async bootstrapping, set up clients/tokens; return a Promise]

↳ render() [idempotent UI write; can be called many times]

↳ if isRenderAsync === true, you must call renderCompleted() when done

↳ onDisplayModeChanged() [called whenever Edit ↔ Read flips; often re-render]

↳ Property Pane open/changes [may trigger render depending on reactive mode]

Page unloads or web part removed

↳ onDispose() [unmount React, remove event handlers, free timers/subscriptions]Let’s walk the hooks the way I use them in production. The constructor runs first and should stay boring. The framework is still wiring things up, so don’t touch the DOM, don’t kick off network calls, and don’t access this.context for anything heavy. I treat the constructor like a place to set plain fields to safe defaults and bind any class methods I know I’ll use. If I’m tempted to do more, that’s usually a smell that it belongs in onInit.

onInit is where I pay the upfront cost once. It runs before the first render and supports asynchronous work, which means I can await token acquisition, prefetch configuration, warm up caches, or hydrate lightweight state. The rule I follow is simple: anything I need exactly once per web part instance and that would otherwise complicate render belongs here. If I need Graph or an API client, I construct it here so render never has to think about how to get data—only how to show it. I also wire telemetry or feature flags here so rendering decisions are a simple if.

render should be predictable enough to read without fear. SPFx may call it multiple times, especially with reactive property panes and display mode flips, so I keep it idempotent and side‑effect free. If I’m using React, this is where I call ReactDom.render with props derived from the property bag and any ready state from onInit. If I’m writing vanilla DOM, I overwrite this.domElement with the exact HTML I want, attach any event handlers, and avoid hidden global state. If I need to do real asynchronous rendering—say I want SPFx to show the loading chrome while I fetch the first page of data—I flip isRenderAsync to true and only call renderCompleted when the first paint is done. The important thing is that render has one job: reflect current state to the DOM as quickly and safely as possible.

onDisplayModeChanged is more subtle than most devs expect. When you switch between Edit and Read modes, SPFx calls this hook. I treat it as a prompt to re-render with different affordances, not as a place to mutate state. For example, in Edit mode I might render a “configure me” hint or unlock controls that are disabled in Read mode. The logic stays in render; the hook just triggers it.

onDispose is where I earn back the memory I borrowed. If I mounted a React tree, I unmount it. If I attached event listeners to this.domElement or window, I remove them. If I started timers, intervals, or Observables, I clear and unsubscribe. This is the number‑one place I’ve seen production web parts leak and cause phantom behavior after navigation. Treat it like cleaning your rack after a heavy set—you don’t skip it, and your future self will thank you.

The property pane sits slightly outside the main flow but drives renders and state updates, so it’s worth understanding the basics first. SPFx can wire property panes in reactive or non‑reactive modes. In reactive mode, each keystroke or control change updates the property bag and triggers render immediately, which is perfect for small, cheap UI updates. In non‑reactive mode, changes apply when users click Apply, which I choose when configuration is expensive or triggers network calls. When the property pane opens, SPFx calls getPropertyPaneConfiguration to build the schema. If you need to keep your base bundle small, you can lazy‑load heavier property pane resources inside loadPropertyPaneResources and then return richer controls. The important mindshift is that property pane changes are inputs; render is still the only place that paints.

Persistence hooks quietly make your upgrades painless. dataVersion tells SPFx what version of your property schema you expect, and onAfterDeserialize lets you migrate user data from older versions safely when the web part loads. I’ve used this to rename fields, split a single property into two, and backfill defaults. onBeforeSerialize runs before SPFx writes the property bag, which is a good place to normalize or strip computed fields so you don’t persist noise. These hooks are basic, but they save you from breaking old pages or writing one‑off migration scripts.

Here’s a concrete set of snippets I reach for when I’m setting up a web part and want to respect the lifecycle boundaries without overthinking it.

// src/webparts/lifecycleDemo/LifecycleDemoWebPart.ts

import { Version, DisplayMode, Log } from '@microsoft/sp-core-library';

import {

BaseClientSideWebPart

} from '@microsoft/sp-webpart-base';

import {

IPropertyPaneConfiguration,

PropertyPaneTextField

} from '@microsoft/sp-property-pane';

import { escape } from '@microsoft/sp-lodash-subset';

export interface ILifecycleDemoWebPartProps {

description: string;

heading?: string; // v2 renamed from "title"

_transient?: string; // computed, not persisted

}

export default class LifecycleDemoWebPart extends BaseClientSideWebPart<ILifecycleDemoWebPartProps> {

private _bootstrapped = false;

public constructor() {

super();

// Keep constructor boring: just field defaults

}

protected async onInit(): Promise<void> {

await super.onInit();

// Example: warm up a client or lightweight config

// const graph = await this.context.msGraphClientFactory.getClient('3');

// this._graph = graph;

Log.info('LifecycleDemoWebPart', 'onInit complete', this.context.serviceScope);

this._bootstrapped = true;

}

public render(): void {

// Idempotent UI write: render can be called many times

const isEdit = this.displayMode === DisplayMode.Edit;

const heading = this.properties.heading ?? this.properties.description ?? 'Lifecycle Demo';

const banner = isEdit ? '<div style="padding:6px;background:#fffae6;border:1px solid #f0c36d;margin-bottom:8px;">Edit mode: configure your web part in the property pane.</div>' : '';

this.domElement.innerHTML = `

<section style="font:14px/1.4 Segoe UI, Arial, sans-serif">

${banner}

<h3 style="margin:0 0 8px 0">${escape(heading)}</h3>

<div>Bootstrapped: ${this._bootstrapped ? 'yes' : 'no'}</div>

<div>DisplayMode: ${escape(DisplayMode[this.displayMode])}</div>

<div>Description: ${escape(this.properties.description || '(empty)')}</div>

</section>

`;

}

protected onDisplayModeChanged(oldDisplayMode: DisplayMode): void {

// Don’t mutate state here; just re-render with different affordances

this.render();

}

protected onDispose(): void {

// If using React: ReactDom.unmountComponentAtNode(this.domElement);

this.domElement.innerHTML = '';

Log.info('LifecycleDemoWebPart', 'Disposed', this.context.serviceScope);

}

// Optional: switch to non-reactive property pane (Apply button)

protected get disableReactivePropertyChanges(): boolean {

return false; // set to true if each change is expensive

}

protected get dataVersion(): Version {

// Bump this when you change property schema

return Version.parse('2.0');

}

protected onAfterDeserialize(deserializedObject: any, dataVersion: Version): void {

// Migrate v1 -> v2: rename "title" to "heading"

const current = Version.parse('2.0');

if (dataVersion.compareTo(current) < 0 && deserializedObject && deserializedObject.title && !deserializedObject.heading) {

deserializedObject.heading = deserializedObject.title;

delete deserializedObject.title;

}

}

protected onBeforeSerialize(): void {

// Strip transient/computed fields before persistence

if (this.properties && '_transient' in this.properties) {

delete (this.properties as any)._transient;

}

}

// Lazy-load heavy property pane resources if needed

protected async loadPropertyPaneResources(): Promise<void> {

// Example: await import(/* webpackChunkName: 'property-pane-helpers' */ './propertyPaneHelpers');

}

protected getPropertyPaneConfiguration(): IPropertyPaneConfiguration {

return {

pages: [

{

header: { description: 'Basic settings' },

groups: [

{

groupName: 'Content',

groupFields: [

PropertyPaneTextField('description', {

label: 'Description',

placeholder: 'Type something descriptive'

}),

PropertyPaneTextField('heading', {

label: 'Heading (migrated from "title" in v1)',

placeholder: 'Displayed as the H3'

})

]

}

]

}

]

};

}

}If you want SPFx to show the loading chrome while you fetch during the first paint, flip on asynchronous rendering. I only do this when I truly need the framework’s built‑in loading affordance; otherwise I keep render synchronous and keep the first paint cheap.

protected get isRenderAsync(): boolean {

return true;

}

public render(): void {

// Kick off async fetch, then paint and notify SPFx

this._fetchFirstPage()

.then(data => {

this._state = data;

this._renderDom();

})

.finally(() => {

// Important: tell SPFx we're done

this.renderCompleted();

});

}If you’re using React, the lifecycle stays the same; the only difference is that render becomes a bridge. The web part owns when to render; your React component owns what to render. I like to keep the prop surface small and derived from the property bag and any initialized clients.

// Inside your web part class

import * as React from 'react';

import * as ReactDom from 'react-dom';

private _renderDom(): void {

const element = React.createElement(MyComponent, {

description: this.properties.description,

heading: this.properties.heading,

isEdit: this.displayMode === DisplayMode.Edit

});

ReactDom.render(element, this.domElement);

}

protected onDispose(): void {

ReactDom.unmountComponentAtNode(this.domElement);

}A few patterns and pitfalls are worth calling out from experience. I never fetch data inside render. If render calls a network, you’ve just linked UI churn to latency and made retries unpredictable. I fetch in onInit, cache the result in a field, and make render a pure projection of that state. If I truly need to fetch on render for the first paint, I use isRenderAsync and call renderCompleted so SPFx can do its job. I avoid attaching global event listeners in render because re‑renders will duplicate them; if I have to attach them, I either attach once in onInit with a teardown in onDispose, or I ensure I remove existing handlers before adding new ones. I keep display mode logic rooted in render so flipping between Edit and Read is just a regular re-render, not a state mutation party. I treat the property pane as a pure source of truth and rely on SPFx to update this.properties; I only override onPropertyPaneFieldChanged when I need to derive one property from another or normalize inputs. And when I change my property schema, I bump dataVersion and migrate in onAfterDeserialize instead of trying to special‑case legacy data in every render. It sounds like extra ceremony once, but it buys back predictable behavior in the long run.

Performance and security ride shotgun with lifecycle decisions. By doing heavy setup in onInit and keeping render cheap, you reduce jank and stabilize P75/P95 times on busy pages. I log the time from onInit start to first render to keep myself honest, and I treat SPFx’s built‑in lazy-loading for property pane resources as a way to keep my main bundle lean. On the security side, when I use AadHttpClient or MSGraphClient, I acquire clients in onInit and never persist tokens in properties or local storage. I also respect throttling and failure modes by caching per‑instance and backing off on errors rather than hammering APIs from reactive property changes. The lifecycle helps because there’s a clean “once” phase and a clean “render often” phase to separate concerns.

Testing and debugging don’t have to fight the framework either. I pull pure functions—like property migrations—into module‑level helpers so I can unit test them in isolation without a SPFx test harness. For example, I’ll write a migrate function that takes a POJO and returns a migrated POJO, then call it from onAfterDeserialize. I use the local workbench and page workbench to observe the render sequence and log with the Log utility so I’m not sprinkling console.log everywhere. If I need to profile, I wrap render in a timing guard and track how often it’s called during property edits so I can justify switching to non‑reactive property panes when edits are expensive.

Here’s a tiny test-friendly example of a migration helper and a Jest test for it. You’ll wire this helper into onAfterDeserialize in your web part, same as above.

// src/webparts/lifecycleDemo/migrate.ts

export interface PropsV1 { title?: string; description?: string; }

export interface PropsV2 { heading?: string; description?: string; }

export function migrateV1ToV2(input: PropsV1): PropsV2 {

if (!input) return {};

const output: PropsV2 = { description: input.description };

if (input.title && !output.heading) output.heading = input.title;

return output;

}// src/webparts/lifecycleDemo/migrate.test.ts

import { migrateV1ToV2 } from './migrate';

test('renames title to heading and preserves description', () => {

const v2 = migrateV1ToV2({ title: 'Old', description: 'Desc' });

expect(v2.heading).toBe('Old');

expect(v2.description).toBe('Desc');

});If you’re just getting started, spin up a fresh project with the generator, drop in the web part skeleton above, and watch the logs as you open and tweak the property pane, flip display modes, and remove the web part from the page. Seeing the lifecycle in motion is what made it second nature for me. Once you stop fighting it and lean into each hook for its one job, your web parts get faster, leaks disappear, and Friday deployments feel a lot less risky.

If this helped you tame your web parts, subscribe for more deep dives and hard-won lessons. I drop new posts that save you hours in the trenches.

- Subscribe: https://wordpress.com/reader/site/subscription/61236952

- Drop a comment with your questions or your own war stories—I read every one.

- Want direct help on your SPFx build? Contact me: https://bdking71.wordpress.com/contact/

Sources

- SharePoint Framework web part lifecycle (Microsoft Docs)

- BaseClientSideWebPart class API (Microsoft Docs)

- DisplayMode enum (Microsoft Docs)

- IPropertyPaneConfiguration (Microsoft Docs)

- Working with the Property Pane (Microsoft Docs)

- Use AadHttpClient in SPFx (Microsoft Docs)

- Call Microsoft Graph in SPFx (Microsoft Docs)

- Version class for dataVersion (Microsoft Docs)

- Build SPFx web parts with React (Microsoft Docs)

- Set up your SharePoint Framework dev environment (Microsoft Docs)

- Debug SharePoint Framework solutions in VS Code (Microsoft Docs)

- Use web part properties in solutions (Microsoft Docs)

- Serve your web part in the workbench (Microsoft Docs)

- Bundling and performance in SPFx (Microsoft Docs)

- Handle lifecycle events in web parts (Microsoft Docs)

Disclaimer:

The views and opinions expressed in this post are solely those of the author. The information provided is based on personal research, experience, and understanding of the subject matter at the time of writing. Readers should consult relevant experts or authorities for specific guidance related to their unique situations.